Building muscle is simple. Lift heavy things, rest, make sure you eat enough food, sleep, repeat. For a beginner, progress is linear and relatively sudden. You get quick feedback: your muscles get more defined, you look a little leaner, you can lift a little more each session, friends and co-workers notice and comment on the changes. New striations pop up, clothes fit differently, you feel more capable dealing with the physical world. You’re hungrier and heavier, yet still manage to drop belt sizes. All is well.

Building muscle is simple. Lift heavy things, rest, make sure you eat enough food, sleep, repeat. For a beginner, progress is linear and relatively sudden. You get quick feedback: your muscles get more defined, you look a little leaner, you can lift a little more each session, friends and co-workers notice and comment on the changes. New striations pop up, clothes fit differently, you feel more capable dealing with the physical world. You’re hungrier and heavier, yet still manage to drop belt sizes. All is well.

Muscle isn’t the only thing you’re impacting when you lift heavy things, though. You’re also imposing stress on your tendons and demanding an adaptive response. You’re training your tendons, too.

Yet because tendons receive less blood flow than muscle, and blood brings the nutrients and satellite cells used to repair and rebuild damaged tissue, they take a lot longer to respond to training than muscle. In one study, it took at least 2 months of training to induce structural changes in the Achilles’ tendon, including increases in collagen synthesis and collagen density. Other studies have found that it takes “weeks to months” of training to increase tendon stiffness. Meanwhile, we see structural changes to muscle tissue with just eight days of training.

This basic physiological fact shouldn’t impede our progress and tissue health, but it does.

Our bodies “expect” a lifetime of constant, varied movement. From a very early age, most humans throughout history were constantly active. They weren’t exercising or training, per se, but they were doing all the little movements all the time that prepare the body and prime the tendons to handle heavier, more intense loads and movements: bending and squatting and walking and twisting and climbing and playing and building. It was a mechanical world. The human body was a well-oiled machine, lubed and limber from daily use and well-prepared for occasional herculean efforts.

We don’t have that today. It’s the age of information. And though we spend most of our day in the digital realm, clacking away on keyboards and caressing touch screens, we retain the ancient need for physical training ingrained in our DNA. So we go from couch potato to budding powerlifter, from desk jockey to CrossFitter. But unlike our predecessors, we haven’t applied the lube of daily lifelong movement that makes those intense physical efforts safe. Everyone seems to be lifting weights nowadays, but few have the foundation of healthy, strong, durable connective tissue necessary for safe, effective training.

Just look at kids. The health of their connective tissue has three main advantages over adults:

They practice constant varied movement. They’re flopping down in distress because you turned the TV off. They’re climbing the bookcase, crawling like a dog, leaping like a frog, dancing to every bit of music they hear, jumping from objects twice their height.

They’re still young. Kids simply haven’t been alive long enough to accumulate the bad habits that characterize sedentary life and ruin our connective tissues. They aren’t broken yet.

Their connective tissue is highly vascular. Early connective tissue has a dense network of capillaries, meaning it receives ample blood flow. It regenerates quickly and has a faster response to stress. Mature tendons are mostly avascular and receive very little blood. To stay healthy and heal and respond to stress, they require diffusion of the synovial fluid filling our joints. Vascular blood flow is passive and subconscious; it’ll happen whether you move or will it to or not. Synovial fluid only diffuses through movement. You have to consciously move your joints to get the synovial fluid flowing.

So what can we do?

“Just move constantly like a six year old” is nice and all, but not everyone can crawl through the office, practice broad jumping across the board room, or run the stairwells with a software engineer on their back. Besides, we have a lot of catching up to do. More concerted, targeted efforts are required to overcome a lifetime of linear, limited movement and tons of sitting.

Before we make any decisions, let’s understand exactly what tendons do.

- They attach muscles to bones. It is through tendons that muscles transmit force and make movement possible. Contracting your muscles pulls on the tendons, which yanks on the bone, producing movement.

- Tendons also provide an elastic response, a stretch-shortening recoil effect that helps you jump, run, lift heavy things, and absorb impacts. Think of it like a rubber band.

Tendons have two primary properties that determine how they function:

Stiffness

The degree to which a tendon can withstand elongation and maintain form and function when placed under stress. Contrary to how we usually think about stiffness, a stiff tendon can help us transmit more force and be more stable in our movements. It takes a lot more force to get a stiff tendon to elongate, but they reward your efforts with a powerful recoil.

Stiff tendons are stiff. More elastic tendons are compliant. We need a mix of compliant and stiff tendons, depending on the tendon’s location and job.

Hysteresis

The efficiency of the recoil response. If you waste a lot of energy in the rebound, you have high hysteresis. If your recoil is “snappy,” your tendons have low hysteresis. Low is better.

Other things matter, of course, like where the tendon “attaches” to the muscle. The farther it attaches from the axis of rotation, the stronger you’ll be (imagine holding the baseball bat in the center or the handle and trying to swing; which grip position will allow greater force?). Another is length; longer tendons have greater elastic potential than shorter ones, all else being equal. But that’s determined by genetics and out of our control.

What can you do to optimize these properties? There are some possibilities.

1. Eccentrics

Many studies indicate that eccentric exercises (lowering the weight) are an effective way to treat tendon injuries. In one trial, ex-runners in their early 40s with chronic Achilles’ tendonitis were split into two groups. One group had conventional therapy (NSAIDs, rest, physical therapy, orthotics), the other did eccentric exercises. Exercisers would do a calf raise (concentric) on the uninjured foot and slowly lower themselves on the injured foot (eccentric heel drop) for 3 sets of 15 reps, twice a day, every day, for 12 weeks. Once this got easy and pain-free, they were told to increase the resistance with weighted backpacks. After 12 weeks, all the ex-runners in the exercise group were able to resume running, while those in the conventional group had a 0% success rate and eventually needed surgery.

If heel dips can heal Achilles’ tendinopathy and single-leg decline eccentric squats can heal patellar tendinopathy, I’d wager that eccentric movements can strengthen already healthy tendons. Any tendon should respond to eccentrics. Downhill walking, slowly lowering oneself to the bottom pushup position, eccentric bicep or wrist curls; anything that places a load on the muscle-tendon complex while lengthening it should improve the involved tendons.

2. Plyometrics

Explosive movements utilizing the recoil response of the tendons can improve that response. In one study, 14 weeks of plyometrics (squat jumps, drop jumps, countermovement jumps, single and double-leg hedge jumps) reduced tendon hysteresis. The trained group had better, more efficient tendon recoil responses than the control group. Tendons didn’t get any bigger or longer; they just got more efficient at transmitting elastic energy. A previous 8-week plyometric study was unable to produce any changes in tendon function or hysteresis, so you need to give it adequate time to adapt.

3. Explosive isometrics

Explosive isometric training involves trying to perform an explosive movement against an immoveable force, like pushing a car with the parking break on, trying to throw a kick with your leg restrained by a belt, or placing your fist against the wall and trying to “punch” forward. In one study, explosive isometric calf training 2-3 times a week for 6 weeks was just as good as plyometric calf training at increasing calf tendon stiffness and jump height while being a lot safer and imposing less impact to the joints.

4. Volume-increasing exercises

Volume clearly matters. Just look at the beefy fingers of free climber Alex Honnold, who relies on them every day to support his bodyweight. Those aren’t big finger muscles. They’re thick cords of connective tissue. Pic not enough? In performance climbers with at least 15 years experience, the finger joints and tendons are 62-76% thicker than those of non-climbers. And a study showed that the extremely common crimp hold—where all five finger tips are used to hold a ledge—exerts incredible forces on the finger connective tissues, spurring adaptation. So if you’re up to the challenge, rock climbing (indoor or outdoor) is a great way to increase tendon volume.

5. Intensity-focused exercises

You have to actually stress the tendons. We see this in the eccentric decline squat study mentioned earlier, where decline squats (which place more stress on the patellar tendon) were more effective than flat squats (which place less stress on the patellar tendon) for fixing patellar tendinitis. In another study, women were placed on a controlled bodyweight squat program. They got stronger, their musculature improved, and their tendons grew more elastic, but they failed to improve tendon stiffness, increase tendon elastic storage capacity, or stem the age-related decline in tendon hysteresis. The resistance used and speed employed simply weren’t high enough to really target the connective tissue. A recent study confirms that to induce adaptive changes in tendon, you must apply stress that exceeds the habitual value of daily activities. So, while walking, gardening, and general puttering about is great for you, it’s probably not enough to coax an adaptive response out of your ailing tendons. You need to increase the magnitude of the applied stress through tinkering with volume, speed, resistance, range of motion, and the proportion of eccentric vs. concentric movement.

6. Full range of motion

Deeper, longer, farther is probably best. Consider the squat. An ass-to-grass front squat, where the hip crease drops below the knees, will stretch/stress the patellar tendon that attaches the quad to the shin bone to a greater extent than squatting to just above parallel.

7. Avoid pain, seek mild discomfort

Tendon discomfort is okay. Stress isn’t comfortable. Tendon pain is not and should be avoided. You want just enough discomfort to provoke a training stimulus, but not outright pain.

8. Daily practice

Think about—and train—your connective tissue every day. That could range from random sets of eccentric heel drops and static squat holds done throughout the day. I like Dan John’s “Easy Strength” program, where you basically pick a few movements to do each day—every day—with a fairly manageable weight. Front squat, Romanian deadlift, and pullups, for example. 2 sets of 5 reps each day for each exercise. Only add weight when it feels “too easy.”

9. Don’t rush; take it easy

Pick a load and stick to it until it gets easy. In a pair of incredible appearances on Robb Wolf’s Paleo Solution Podcast, Christopher Sommer of Gymnastic Bodies explains how he puts together a tendon-centric program for an athlete. He has them stick with the same weight for 8-12 weeks. The first few weeks are hard. The weight feels heavy. At 4 weeks, it’s a lot easier but still a challenge. At 8 weeks, you start feeling like it’s too easy. And that’s where the tendon-building magic happens. By 12 weeks, what felt tough when you started is now “baby weight.” Your muscles are stronger and your tendons have had enough time to build collagen density. You’re able to manhandle the weight without a problem.

Like I just mentioned above, another example is Dan John’s “Easy Strength,” which has you lift almost every day using light-moderate loads, only adding weight when 2 sets of 5 reps becomes really easy. You won’t see the rapid progression of Starting Strength, but it’ll also be easier on your body, prepare your tendons for higher loads, and remove the need for a gallon of milk a day.

10. Partial reps

Early 20th century strongman George Jowett developed a program for “strengthening the sinews” that involved partial reps of extremely heavy weights. He focused on the final 4-6 inches before lockout of the primary exercises, like bench press, overhead press, squat, and deadlift.

11. Massage and myofascial work

Massages can increase blood flow to the otherwise avascular tendons. Self myofascial release using foam rollers or lacrosse balls (or even the good ol’ elbow) is worth doing, too.

Building connective tissue strength isn’t just for preventing injuries. It will make you stronger, too. Every person aged 16 to 28 knows about “old man strength.” It’s that phenomenon of otherwise unimpressive looking old guys crushing your hand when shaking it, being immovable statues down low in pickup basketball games, and generally tossing you around like you were a child in any feat of strength. What explains it? It’s not the muscles (yours are bigger). It’s not the speed (you’re younger and faster). It’s gotta be the connective tissue made thick and strong from decades of hard living.

And so in real-world, full-body movements and compound exercises like squats, deadlifts, pullups, and gymnastics work, healthy and strong tendons increase performance. They make you stronger, more explosive, more powerful, and more resilient. They allow your big impressive muscles to actually express themselves and reach their full potential. A healthy tendon is a conduit for your muscle to express its power.

Muscles are cool and all, but don’t neglect the tendons. Feel the stretch and when you feel some weirdness in a tendon, back off. Throw in some eccentric movements and explosive isometrics. Practice hops and broad jumps. Do a joint mobility drill regularly, and consider adding a morning movement practice. Don’t feel guilty for not going hard all the time. Get really comfortable with the weight and the movements before increasing the intensity.

There’s more to the tendon story, but these are a few easily implementable suggestions for improving your tendons with physical training.

Thanks for reading, everyone. How do you train your tendons? Have you ever considered such a thing?

Read more: http://www.marksdailyapple.com/why-training-your-tendons-is-important-and-11-ways-to-do-it/#ixzz4IkcLCCAi

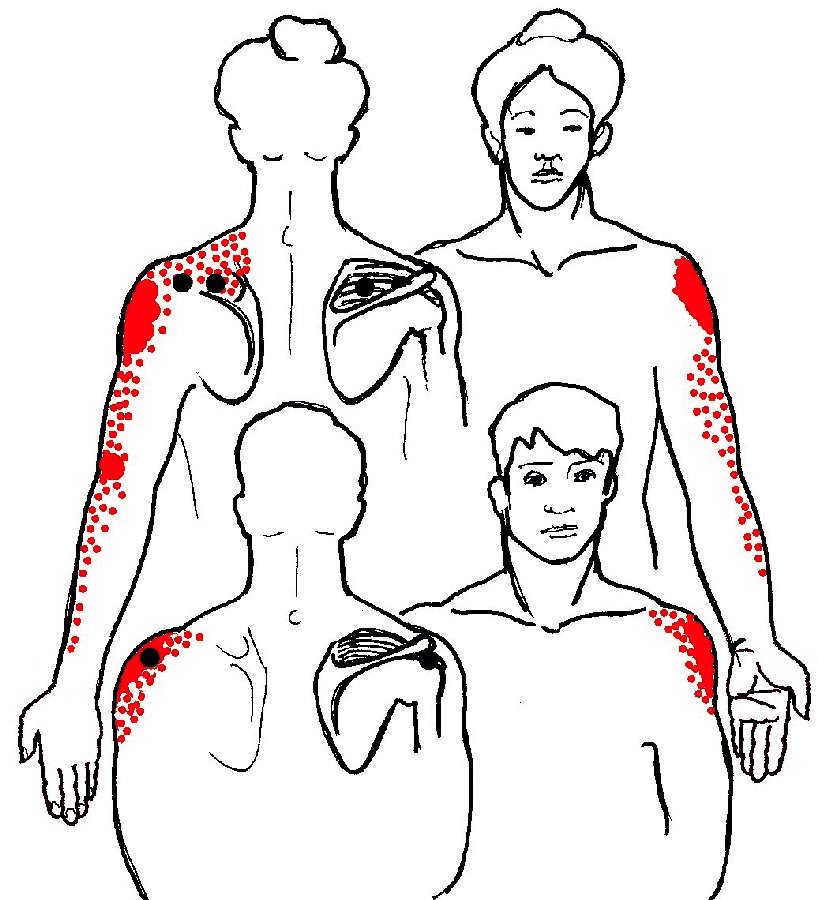

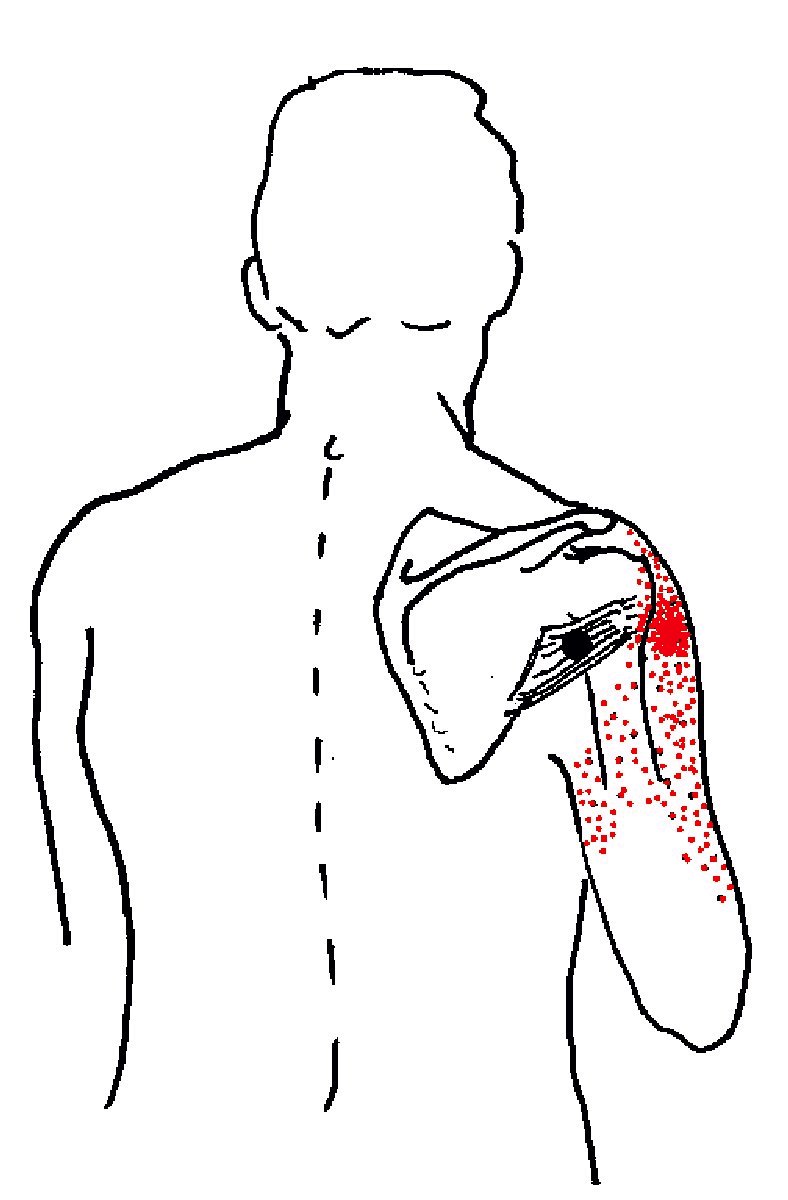

You may think you're having a heart attack. Get it checked!

You may think you're having a heart attack. Get it checked! the scapula," strongest on outside of shoulder. It extends down the arm to the elbow and possibly along the lateral (thumb side) of the forearm. Commonly strained in association with infraspinatus.

the scapula," strongest on outside of shoulder. It extends down the arm to the elbow and possibly along the lateral (thumb side) of the forearm. Commonly strained in association with infraspinatus. the back is a very common source of pain on the lateral and front side of the shoulder. Pain is felt deep in the shoulder joint, primarily at the front of the shoulder. Pain may extend down lateral (thumb side) and anterior ("fishbelly") side of the arm as far as the front and back of the hand. Commonly injured in sudden abrupt arm movements such as catching oneself when falling backwards or excessive poling while skiing.

the back is a very common source of pain on the lateral and front side of the shoulder. Pain is felt deep in the shoulder joint, primarily at the front of the shoulder. Pain may extend down lateral (thumb side) and anterior ("fishbelly") side of the arm as far as the front and back of the hand. Commonly injured in sudden abrupt arm movements such as catching oneself when falling backwards or excessive poling while skiing. rotator cuff and a major player in the garbage-can diagnosis known as "frozen shoulder."

rotator cuff and a major player in the garbage-can diagnosis known as "frozen shoulder." to the back of the arm, apparently deep in the posterior deltoid. It may refer pain up to the shoulder and numbness and tingling down to the fourth and fifth (ring and pinky) fingers. Teres minor rotates the arm laterally and is the smallest and most "minor" of the rotator cuff muscles working in concert with the infraspinatus.

to the back of the arm, apparently deep in the posterior deltoid. It may refer pain up to the shoulder and numbness and tingling down to the fourth and fifth (ring and pinky) fingers. Teres minor rotates the arm laterally and is the smallest and most "minor" of the rotator cuff muscles working in concert with the infraspinatus. “major muscle of the chest.” The shoulder, arm, and chest pain of this muscle suggest serious disease. In women, breast pain is feared to be due to breast cancer and patients may be sent for repeated mammograms (ironically, exposing them to additional radiation). Tight pectorals can also cause shoulder and chest pain extending down the arm to below the elbow. In both men and women, this pattern (especially when on the left side) can be terrifyingly similar to the pain of angina and heart attack. Pectoralis major is strained or shortened by: Hunching shoulders forward, sitting or sleeping with arms crossed on chest, typing / keyboarding, sword work.

“major muscle of the chest.” The shoulder, arm, and chest pain of this muscle suggest serious disease. In women, breast pain is feared to be due to breast cancer and patients may be sent for repeated mammograms (ironically, exposing them to additional radiation). Tight pectorals can also cause shoulder and chest pain extending down the arm to below the elbow. In both men and women, this pattern (especially when on the left side) can be terrifyingly similar to the pain of angina and heart attack. Pectoralis major is strained or shortened by: Hunching shoulders forward, sitting or sleeping with arms crossed on chest, typing / keyboarding, sword work.