In every issue of our journal you will find Case of the Month which we will select among submitted ones. Everyone who is using Medical Massage protocols in their practice may submit their cases for the review and we will share with our readers the best one in every new issue.

If you would like to share with our readers your account of professional success and participate in Case of the Month program click here.

This case of the month is submitted by Cory Fairchild, LMT. Cory specializes in sports massage, preparing young gymnasts for optimal performance. His submission illustrates the important point that differentiates sports massage from medical massage. Unfortunately, this issue is frequently misunderstood. Many times we read articles or Internet posts in which authors treat shoulder injuries or knee injuries with sports massage.

Sports massage is used to enhance training and athletic performance but only when the athlete or sports enthusiast is free from the injury. When an athlete is injured, a massage practitioner should switch gears and move to a completely different approach using the appropriate protocol of medical massage. For example: The rotator cuff damaged during a tennis game is similar to the rotator cuff injury of construction worker.

Cory shares a similar vision, and he is equipped with the understanding and the professional knowledge necessary to assist athletes in any possible way they need.

Dr. Ross Turchaninov, Editor in Chief

MEDICAL MASSAGE vs SPORTS INJURY

by Cory Fairchild, LMT

This case study deals specifically with the proper evaluation of an incident of shoulder pain in the sport of Men’s Artistic Gymnastics. The client athletes are 17- and 18-year-old gymnasts of the USA Gymnastics Junior Olympic and/or Junior Elite divisions. While not all of the athletes are JR. National Team members, it is important to note that their general physical preparation (GPP) is close enough to be considered a constant with the primary difference being the rate of progression through their conditioning. Technical skill varies, however, as it is not due to a difference in GPP, it is considered irrelevant to this study.

The athletes’ GPP consists of physical conditioning and mobility (defined as exercises that promote structural balance, joint integrity, or the ability of a muscle to express strength through its full of range of motion). The combination of GPP and technical training constitutes in excess of twenty-four to twenty-six hours per week. It is important for the purposes of this case study to note that general physical preparation is geared towards maximal contraction in muscles rather than muscular fatigue. In addition to their gymnastics training, each week the athletes receive a minimum of one full-body massage according to Russian Sport Massage protocols, with supplemental massage available on the third training day after.

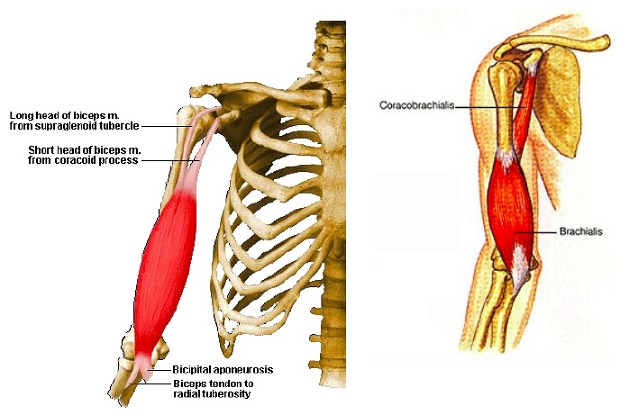

To properly understand this case study, it is also necessary to address the relevant anatomy as relating to Men’s Artistic Gymnastics. While gymnastics as a necessity relies on the whole body to produce both isotonic and isometric contractions, the rings apparatus is unique in that the ability of an athlete to progress static holds depends entirely on the strength of the biceps brachii and brachialis tendons to keep the elbow locked and allow leverage from a fully straightened arm. As tendons heal at roughly 1/10th the rate of muscle tissue, great emphasis and care is placed on this particular structure. An improperly developed tendon will prevent an athlete from expressing the body shape needed for static strength elements on the rings apparatus. Inversely, strong tendons can at times bear additional load while an athlete is developing proper body shape on advanced static elements such as a Maltese cross (e.g., athlete cannot produce sufficient scapular protraction). Fig. 1 illustrates the anatomy of biceps brachii and brachialis muscles. Note the insertion point of the biceps brachii and brachialis in relation to the elbow joint.

Fig. 2 illustrates one of our athletes doing the Iron Cross. Clearly visible is the amount of stress elicited on the entire upper body, especially at the insertion of the biceps brachii and the brachialis muscles (depicted by the red arrow).

Client Complaints and Evaluation

The athlete experienced anterior shoulder pain during practice. Examination revealed that the pain was specifically at the attachment of the short head of biceps brachii and the coracobrachialis on the coracoid process. In addition, the athlete experienced restricted range of motion when putting the arm into internal rotation. At that time, the athlete was administered efflourage and PIR stretching and scheduled for specific treatment sessions. During the first specific treatment session, the athlete was evaluated for Musculocutaneous Nerve Neuralgia (MCN). This evaluation was chosen for two reasons: first, as the athlete had recently increased their ring-strength work and therefore involvement with the biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis would be highly suspect. Secondly, upon prompting for a description of all related problems with the shoulder and arm, the athlete recalled experiencing forearm pain that matched the chart for C6 dermatomes. The tissue evaluation yielded tension in the pec minor, trigger points in the coracobrachialis, brachialis, and biceps brachia muscles, as well as hyperalgesia in the aforementioned dermatomes.

Treatment

Treatment was administered over the course of three specific sessions. The protocol for MCN was used from the Medical Massage Textbook (p.298) with regards to cutaneous reflex zones, Pectoralis Minor Muscle Syndrome inclusion, trigger point therapy, and Postisometric Muscular Relaxation (PIR). The most dramatic relief came from the initial session, with the two follow-up sessions reinforcing the elimination of the reflex zones.

The athlete was able to continue training without interruption during the period of specific treatments and reported a cessation of pain by the end of the last treatment.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий